Digital Health Applications Ordinance (DiGAV, Digitale-Gesundheitsanwendungen-Verordnung): What Manufacturers Should Know

Tuesday, April 21, 2020

On April 17, 2020, the German Federal Ministry of Health (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit) presented the preliminary draft of the Digital Health Applications Ordinance, the DiGAV for short. The DiGAV establishes the requirements for the reimbursement of digital health applications (DiGA) by health insurance companies.

Find out what requirements the ordinance establishes for manufacturers so that you can decide whether an application is worthwhile and whether the costs involved are proportional to the expected economic benefits.

This understanding will help you submit a successful application and help you make money from your DiGA as soon as possible.

The BfArM (German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices) has published guidance in parallel to the DiGAV. The guidance also reveals the US tech group you should avoid if you want to meet the requirements of the DiGAV. You can read more about this in section 6 “DiGAV requirements with regard to devices.”

Download

Download the Digital Health Applications Ordinance (DiGAV) and the BfArM’s DiGA guidance here.

1. DiGAV: what is it?

The full name of the DiGAV is: “Ordinance on the procedure and requirements for assessing the reimbursability of digital health applications in statutory health insurance.”

This ordinance establishes how the “Digital Care Act (DVG, Digitale-Versorgung-Gesetz)” should be implemented. The DVG already specifies the most important requirements for digital health applications:

- The device must be a class I or IIa medical device (according to the MDR or MDD).

- It must meet the data protection and interoperability requirements, among others.

- The manufacturer must demonstrate positive care aspects.

- The manufacturer must make a successful application to the BfArM for inclusion in the “Directory of reimbursable digital health applications according to §33a.”

Further information

Read more on the Digital Care Act (DVG) here.

The DiGAV describes how manufacturers can demonstrate that their devices meet the legal requirements more precisely than the DVG. For example, the ordinance contains specific checklists that manufacturers must use to verify that they have complied with the IT security requirements.

Unlike the act, the ordinance also regulates the costs and precise content for the electronic directory as well as the procedure for inclusion.

2. DiGAV overview

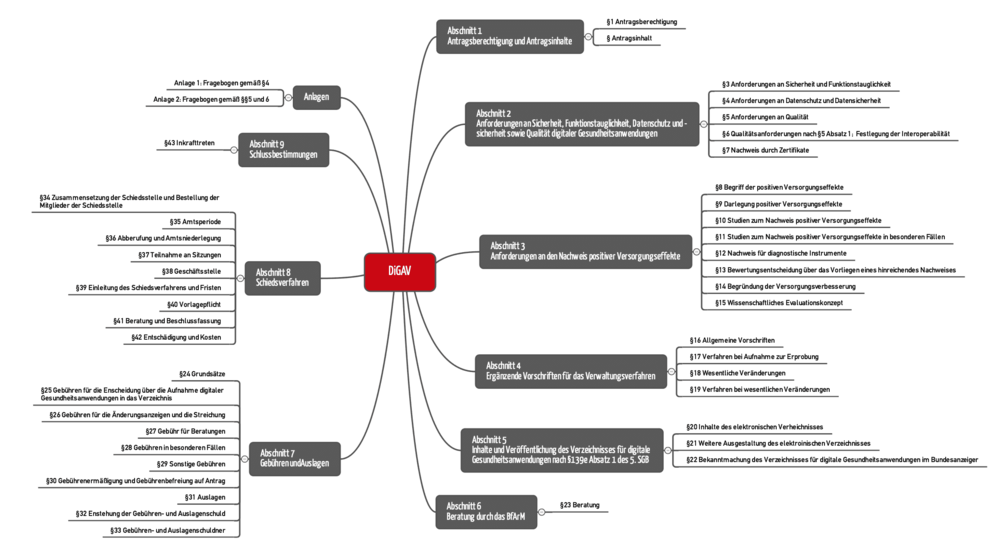

The DiGAV comprises 43 paragraphs divided into 9 sections (see Fig. 1).

Sections 2, 3 and 5 are particularly relevant for manufacturers:

- Section 2 establishes the requirements for DiGA, e.g., with regard to data security, interoperability and quality.

- Section 3 describes how manufacturers have to demonstrate that their device has a “positive care aspect.”

- The content that the manufacturer has to publish in the “DiGA directory” is established in section 5.

Further information

You can read here what the Digital Care Act considers a positive care aspect and what examples there are.

3. When can you start making money with DiGAs?

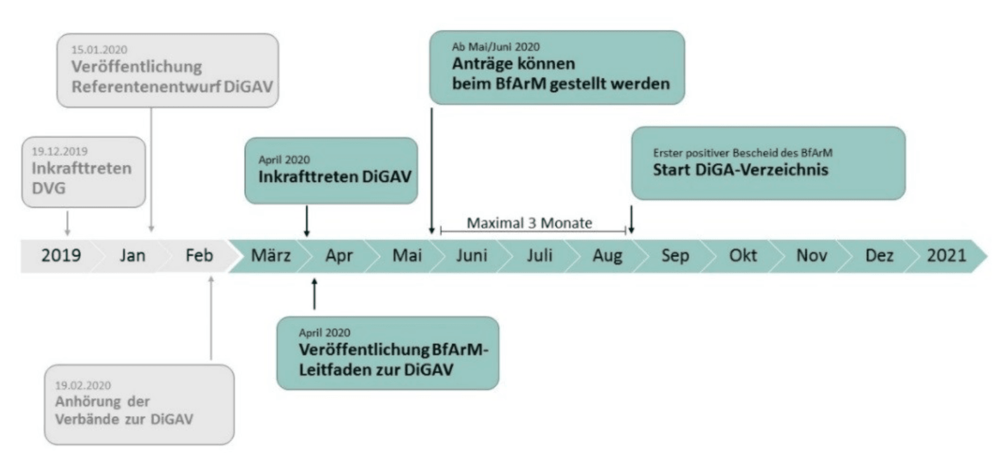

The German government seems to want to allow manufacturers to benefit quickly from the reimbursement of their DiGAs. The BfArM writes: “The procedure is designed as a rapid “fast-track” procedure.”

It doesn’t make it clear whether "rapid" is a tautology or is qualifying “fast”.

In any case, in its guidance document, the BfArM states that the first DiGAs will be included in the directory in August.

4. What the application costs (sections 24 and the following)

The DiGAV specifies the costs of filing an application. These typically range from EUR 3,000 to 9,900. In the case of a “trial” inclusion in the directory, manufacturers should expect costs of between EUR 1,500 and 6,600.

Consultations cost between EUR 250 and 5,000, with the exception of “general oral, written or electronic information that is minor in scope.”

On request, the BfArM may reduce the fees to as little as a quarter, if for example the manufacturer cannot expect commensurate financial benefits. This would be the case for very small target groups.

5. Digital health applications directory (section 20 and the following)

5.1 Content of the directory (“drop your pants?”)

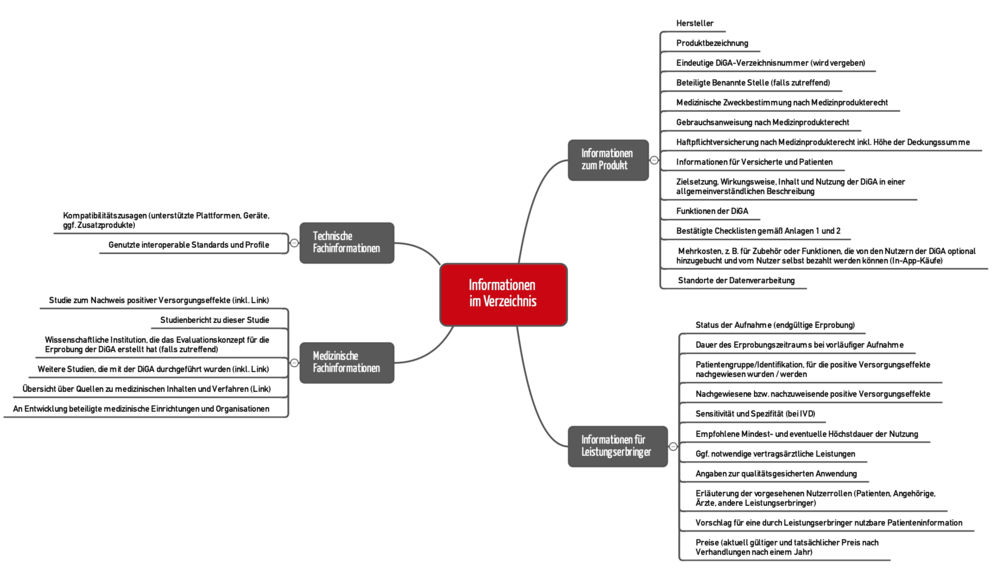

Section 20 of the DiGAV describes the content that has to be published in the digital health applications directory. An even more detailed specification can be found in section 2.2 of the BfArM guidance (see Figure 3).

In some cases, however, providing a link to your own websites where the information can be found is enough.

Manufacturers have to reveal quite a lot. Even the obligation to publish studies and their results as well is a source of irritation for a lot of people. Some manufacturers may be worried that this will force them to reveal confidential business information. With regard to this, the BfArM writes:

During the application procedure, the manufacturer can mark the information whose publication is prevented by legal requirements. Examples include the protection of confidential business information, the protection of the personal data of third parties or the protection of intellectual property.

BfArM DiGA guidance

However, the BfArM insists on a complete application in all cases.

5.2 Directory interfaces

The directory should be publicly accessible. Two interfaces are envisaged:

- “User-friendly and target group-specific structured web portal”

- Application programming interface (API)

The web portal should “provide, in different and clearly presented views, insured persons or physicians with the information that is particularly relevant for them.”

The API should be made available to “other interested public and non-profit institutions.” Here, the BfArM is thinking of “professional associations, health insurance companies, physicians' associations, research institutions, foundations, municipalities, patient associations and other actors.”

However, there are not yet any specifications for the API. “Details of the application programming interface and its use (registration, test accesses etc.) will be published by the BfArM via its website in the course of the year.”

6. DiGAV requirements with regard to devices

6.1 Data security and data protection

Specifications

Manufacturers should not underestimate the importance the legislator is attaching to data security and data protection. This is made clear in the corresponding publications:

- Digital Care Act (DGV)

- Digital Health Applications Ordinance (DiGAV)

- Technical Guideline BSI TR-03161: Security Requirements for Digital Health Applications

The BSI guideline refers in turn to other specifications:

- BSI Standard 200-1, BSI Standard 200-2, BSI Standard 203

- BSI Basic IT Protection Compendium

- BSI TR-02102-1: Cryptographic Mechanisms: Recommendations and Key Lengths

- BSI TR-02102-2: Cryptographic Mechanisms: Use of Transport Layer Security (TLS)

- TR-03107-1: Electronic Identities and Trust Services in E-Government Part 1

Firming up requirements through checklists - and problems with it

The DiGAV (thankfully) clarifies the requirements by offering specific checklists in Annex 1. Unfortunately, these checklists do not appear to be fully aligned with BSI TR-03161.

The annex still only contains only partially useful requirements, such as checking XML or JSON files against defined schemas to protect against DDoS attacks.

This can help, but it can also have exactly the opposite effect: if you check all DDoS attack traffic against schemas first, you bring the server to its knees even faster.

Difference between high and very high protection requirements

The DiGAV's checklist contains points that only DiGAs with “very high protection requirements” have to follow. For example, the ordinance only insists on penetration testing or 2-factor authentication if a very high level of protection is required.

The BSI defines what a very high protection requirement is on page 24 of BS 200-2. It states that there is a very high protection requirement if “the protection of personal data must absolutely be guaranteed.” Failure to do so may result in danger to life and limb or to the personal freedom of the person concerned.”

Data on Amazon servers

It is the BfArM guidance, not the DiGAV, that is the first to be able to bring itself to making halfway concrete statements as to whether manufacturers can use the US tech giants’ cloud services:

Apple is currently not certified under the EU-US Privacy Shield. Amazon (including Amazon AWS), Microsoft (including Azure) and Google (including all services offered by Google LLC) are currently certified by the EU-US Privacy Shield and comply with the rules for non-HR data.

BfArM DiGA guidance

This means that personal data must not be stored in the Apple cloud. Anyone who thinks that they can simply switch to Amazon, with a German data center if necessary, should continue reading the document:

If back-end services are running in a US provider’s commercial cloud, it is not sufficient for the cloud provider to be certified under the EU-US Privacy Shield. As the use of the cloud in this case is based on a processing contract, the DiGA manufacturer’s control over the data processing must also be confirmed by the cloud provider. In this regard, the general terms and conditions of cloud providers often contain clauses that make this more difficult, such that a more detailed analysis of the specific forms of cloud use is, in each case, necessary in the context of a risk assessment.

BfArM DiGA guidance

At this point, the BfArM leaves us on our own a bit. More detailed guidance would have been desirable. For example, it could have provided information on which passages in standard contracts with AWS manufacturers should pay special attention to.

6.2 Interoperability

Goal of interoperability

The interoperability of DiGAs is also close to the legislator's heart. There are several reasons for this:

- Patients should be able to change insurance companies and take their data with them. Otherwise, competition between insurers would be more difficult.

- Healthcare must work across sectors. Otherwise, unnecessary costs are incurred, for example through duplicate examinations, transfers from one system to another, for manual activities, etc.

Interoperability should enable the continuous flow of information between all parties involved in the healthcare system and their IT systems and (medical) equipment. This includes:

- Hospitals

- Registered physicians

- Pharmacies

- Therapists

- Health insurance companies

- Patients (including their own measuring devices, including wearables)

Therefore, the DiGAV establishes specific requirements with regard to interoperability.

Use “top-quality interoperability standards”

Manufacturers are not free to choose interoperability standards.

- They must use an MIO (medical information object) defined by the KBV or a recommended standard in the vesta standards directory or an equivalent profile.

- If there is no suitable standard available in these places, manufacturers must select one of the following options:

- Using existing open, internationally recognized standards, e.g., an FHIR profile defined by HL7.

- Developing their own profile for an existing open international standard or extending a profile. However, this requires the manufacturer to send a request “to gemetik for the inclusion of the resulting interface specification in the vesta directory.”

- Developing their own profile for a standard listed in the vesta directory or extending a profile. This also requires the manufacturer to send a request “to gemetik for the inclusion of the resulting interface specification in the vesta directory.”

Please note!

Either you use a standard (if there is one) or you contribute to extending a standard or creating a new one.

Excellent interoperability standards for medical devices as well

This obligation to use top-quality standards also applies to medical devices, wearables and sensors. The DiGAV gives manufacturers three options.

- They implement “a published and documented ISO/IEEE 11073 profile”

- They use a “standard or a profile listed in the vesta directory”

- The manufacturer develops their “own profile or their own standard and requests this specification to be included in the vesta directory”

However, these requirements only apply if the manufacturer obtains the data directly from a device and not just indirectly via a platform such as Apple's Health Kit.

It is surprising that the BfArM mentions Apple Health of all things, because it itself has just stated that Apple is not Privacy Shield-certified.

Conclusion: The DiGAV continues towards the “standardization of standards”, which is to be welcomed. This will be the end of a lot of proprietary standards.

Which data have to be exchanged

Manufacturers do not have to offer all data via the standardized interfaces. For example, log files, raw data or usage statistics may also be "played out" through proprietary interfaces.

The BfArM has established the following rule of thumb:

The requirement for interoperable, machine-readable export is solely a requirement for interoperability. Interoperability comes before completeness. If an MIO or a standard/profile/guideline recommended in the vesta directory that covers 80% of the information to be exported is known, then this standard/profile/guideline must be used.

BfArM DiGA guidance

6.3 Robustness

The DiGAV and the guidance explain more clearly than the DVG what the legislator understands by “robustness.” It relates to the ability of the system to cope with events such as the following:

- Power supply failure

- Internet connection failure

- The mobile device being switched off

- (Accidental) disconnection of a device

- Incorrect and incomplete system settings

- Problem with hardware, sensors, actuators

- Incorrect entries by user

The BfArM guidance also specifies the consequences that must be avoided if the above events occur:

- Data corruption

- Data loss

- Incorrect (improbable, impossible) data

- Multiple data available

- System in inconsistent state

- Unnecessary costs and effort for users

The guidance even gives some possible actions:

- Check data for plausibility

- Discard incorrect data

- Information or warnings to users

- Use of reference or test data (e.g., images)

- Reset option

6.4 User-friendliness (section 5 paragraphs 5 and 6)

Unfortunately, the DiGAV and the BfArM use the undefined term “user-friendliness”. It is not clear whether they are really talking about usability or operability.

The strong focus on accessibility suggests that usability is what they are referring to. However, the DiGAV distinguishes between the two terms in Annex 2.

References in the guidance to “style guides” and to “holding focus groups” suggest usability in a broader sense. However, this would already have been demonstrated as part of the “authorization” as a medical device.

6.5 Quality assured knowledge (section 5 paragraph 8)

The DiGAV requires:

The medical content used by digital health applications must reflect the generally accepted state of medical knowledge.

DiGAV section 5 (8)

The BfArM concludes that “the medical basis of DiGA must be derived from accepted and reliable sources, such as medical guidelines, established textbooks, equivalent recognized sources or at least published studies.”

7. Evidence of positive care aspects

The biggest headache for manufacturers is likely to be section 3 on the “Requirements for demonstrating positive care effects”.

The definition of the terms “positive care effect”, “medical benefit” and “patient-relevant structural and procedural improvements” and examples can be found in the article on the DVG, even if only the DiGAV and the BfArM give these examples.

Manufacturers of all medical devices must prove that their devices at least reflect the state of the art and are, therefore, equivalent to an alternative device or procedure.

The DiGAV sets the bar higher, as you will find out below.

Challenge 1: the DiGA must be better

The manufacturer must prove that using the DiGA is better(!) than not using it. In this context, not using it means that a patient

- is treated without the DiGA in question but with something else

- is not treated at all or

- is treated with a comparable and already listed DiGA

NB!

As a result, it will not be possible to have an equivalent DiGA included in the DiGA directory. For manufacturers, this means that one who gets there first wins!?

So it is not exactly clear how a situation like the one described here by the BfArM can occur:

If the prescribing physician is not able to discern a difference between two or more DiGAs with regard to the intended therapeutic support in the specific case, it may be necessary in individual cases to prescribe the more cost-effective DiGA.

BfArM DiGA guidance

Challenge 2: the proof must be in the form of a study

The MDR and MDD permit, in the context of the clinical evaluation, the benefit-risk ratio to be demonstrated via literature and, if necessary, even “only” using performance data.

In contrast, the DiGAV always insists on a scientific study.

Challenge 3: the study must be carried out with the DiGA itself

The MDR and MDD are also more generous with regard to the devices used to provide evidence in studies. As long as the equivalent device is clinically, technically and biologically comparable, the data obtained with it may be used for verification.

The DiGAV goes one step further. The BfArM describes the requirement as follows:

References only to other primary literature and studies, even those with equivalent DiGAs, are not permitted.

BfArM DiGA guidance

Challenge 4: the studies must be conducted in Germany

The BfArM comes to the conclusion that “by limiting the studies to Germany, it is ensured that the study results will be sufficiently valid.”

The Johner Institute cannot understand this conclusion. It is precisely by limiting the studies to German that means it may not be possible to collect sufficient data and that the study results may not be sufficiently valid.

Whether study results are valid or not depends on the type and quality of the study and on the comparability of the population, not primarily on the country.

If other countries were to make such demands, this would be denounced as a restriction of competition. We therefore consider it likely that an action will be brought against this aspect of the regulation.

Challenge 5: obligation to publish

The DiGAV stipulates that the studies must be registered and their results published. The BfArM writes:

The studies must be registered with a public study registry. The study registry must be a primary registry or a partner registry of the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform or a data provider to the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. [...] The recognized primary registry for Germany is the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS) managed by the German Institute for Medical Documentation and Information (DIMDI).

Studies submitted for inclusion in the register [must] be published on the Internet with the results 12 months after the completion of the study at the latest. […]

It is important that negative results are also published.

BfArM DiGA guidance

This information is of course also interesting for the competition. If the results enable conclusions to be drawn about business and trade secrets, the relevant passages can be redacted.

8. Conclusion

Summary

It might sound tempting for manufacturers to have their DiGA reimbursed by health insurance companies. But the DiGAV sets the bar very high:

- Manufacturers must demonstrate that the data protection requirements have been met using a checklist.

- Their devices must ensure interoperability, as a general rule through generally recognized standards. Anyone who has never heard of MIOs or a vesta list will almost certainly have a hard time with this.

- The obligation to carry out studies with their own DiGA and the obligation to be better than alternative devices or procedures means high costs for the manufacturers. The requirements of the DiGAV are stricter than the requirements of the MDR when it comes to the clinical evaluation. And manufacturers are already complaining about costs in regard to the MDR.

Approval and criticism

Anyone who wants money from society, i.e., the insured, has to do something. That's a good thing. It is also good that:

- Relatively precise data protection requirements have been established

- The need for “standardized standards” will lead to sector boundaries in healthcare to be knocked down and this will increase efficiency (and hopefully effectiveness)

- The benefit must be proven and that no public money will be spent on applications with questionable benefits - at least in the long term

But questions remain unanswered:

- Why are class IIb and III devices, which often have a particularly high benefit, excluded?

- Why are the IT security checklist items in Annex I of the DiGAV not aligned with BSI TR-03161?

- Why do they think that study results are more valid if the studies are conducted exclusively in Germany?

- How can there be competition between DiGAs if an “equally good” DiGA cannot be included in the directory?

- Why does a manufacturer have to be better than the state of the art? Manufacturers of medical devices already have to demonstrate their medical benefit.

- Why does the DiGAV insist on new studies even for devices that only claim to have a medical benefit and no other positive care aspects?

The decision to set the hurdles so high is a political one that is understandable in terms of patient safety and sensible use of public funds.

But anyone who believes that the DiGAV will help small, innovative start-ups to quickly develop a viable business model will be disappointed. The requirements of the Digital Health Applications Ordinance are immense - and they come on top of the MDR requirements.

Thanks to Sonia Seubert from Dierks + Company who is a lawyer specializing on this topic.

The Johner Institute supports manufacturers on the design and implementation of scientific studies that meet all the DiGAV requirements. Get in touch with us.

News

Amendment to the Digitale Gesundheitsanwendungen-Verordnung (DiGAVÄndV)

The first Verordnung zur Änderung der Digitale Gesundheitsanwendungen-Verordnung (DiGAVÄndV) provides several new features for manufacturers of digital health applications (DiGA):

Summary

The most important features of the amendment for you as a manufacturer:

- The application for listing in the DiGA Directory and the information provided for the directory must be in German.

- There must be a connection to the electronic patient file, taking into account the interface specifications and the requirements in Annex 2.

- Authentication using a digital identity should be possible.

- The requirement for a certificate from the BSI demonstrating proof of compliance with data security AND data protection requirements replaces the self-declaration using Annex 1. This also applies for legacy digital health applications. They should have appropriate resources and take the technical guidelines of the German Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) into account.

- Changes to the DiGAV or the underlying SGB V are actually being made quite quickly. You should set up monitoring (SGB V, DVPMG, DiGAV, DiGAVÄndV) to stay up-to-date and make sure you meet any deadlines (see below).

- Editorial changes to the DiGA Directory are not substantial changes and can be displayed free of charge.

1. Additional information to be included in applications

Information must be added to the application (see DiGAV § 2 Application content) regarding:

- The data processed by the digital health application

- Their representability using international semantic standards

- For requests submitted on or after August 1, 2022, their mappability using the current specifications for the semantic and syntactic interoperability of electronic patient file data

- Human-readable export formats from the digital health application

Implementation notes:

Manufacturers must include these aspects when submitting an application. If the information is not available in German, it must be translated into German (application content, particularly the content that appears in the electronic directory).

Certification now also for data protection and ISMS certification also for legacy digital health applications

Expansion of “§ 4 Data protection and data security requirements” and “§ 7 Proof through certificates”: From April 1, 2023, digital health applications must provide proof of compliance with the data protection requirements by submitting a test certificate (e.g., from the BSI). This means that the self-declaration using Annex 1 will no longer be sufficient. § 7 clarifies that the obligation to have an operational and certified information management system from April 1, 2022 also applies for already listed digital health application manufacturers.

Implementation notes:

The technical guideline of BSI TR-03161 contains an explicit catalog of requirements for measures to be implemented. This will probably also form the basis for the test criteria. For data security, a test certificate from the BSI was already required as a result of the last amendment. This now applies for data security AND data protection. This means one certificate is needed for the ISMS (e.g., ISO 27001), another for proof that the digital health application complies with the data security requirements, and a third certificate to prove that the digital health application meets the data protection requirements. Plan accordingly for legacy digital health applications as well.

Interoperability requirements

Addendum to “§ 6 Interoperability”: Paragraph 355, which requires specifications for the semantic and syntactic interoperability of data for the electronic patient file, has been added to SGB V. The National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians will publish corresponding specifications by June 30, 2022. Until then, open, internationally recognized interfaces and semantics standards can also be used.

Electronic patient file (ePA)

Addition to “§ 6a Interoperability of digital health applications with the electronic patient file”: From January 1, 2023, digital health applications must be able to transmit the processed data – with the consent of the insured person – to the insured person's electronic patient file, i.e., have a corresponding interface specified by the Gesellschaft für Telematik. Semantic and syntactic interoperability must be taken into account. Manufacturers will have 6 months to implement the semantic and syntactic data interoperability requirements once they have been published by the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians.

Implementation notes:

Close monitoring of changes in interface specifications and statutory digital health application requirements as a whole should be planned as part of the post-market surveillance (PMS) activities. Automatic change notifications are recommended. Additional specifications also have to be written (e.g., for secure identity).

From January 1, 2023, the electronic patient file (ePA) must be supported by the manufacturer. The Gesellschaft für Telematik will produce specifications for the interface by January 1, 2022. You can see the changes here.

Concretization of substantial changes

Change notification: It specifies what are not substantial changes, namely “changes to the data and information that are minor in scope and merely editorial in nature” in the DiGA directory. These changes can be reported to BfArM through a simple notification. Previously, all changes to “data and information published for digital health applications in the directory” were considered substantial changes. It also adds that this “simple notification” is exempt from the fee schedule.

Editorial changes

- Information regarding deadlines that have already passed has been removed (e.g., "by January 1, 2021 at the latest”).

- It is specified that “interoperability” means syntactic and semantic interoperability.

- The interoperability directory according to § 291e of the SGB V is now the interoperability directory according to § 385 of SGB V (§ 291e of the SGB V has been deleted).

- The reference to SGB V § 291b paragraph 1 sentence 7 is replaced by SGB V § 355 paragraph 2a in which it now states that the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians will publish the necessary specifications for semantic and syntactic interoperability of data from digital health applications transmitted to the electronic patient file by June 30, 2022.

Changes to the annexes

- Annex 1, Data protection, number 13. The question of whether data stored and files created locally on the IT system used are securely deleted after the digital health application use session is ended even if the person using the session does not explicitly end it has been deleted. Therefore, no proof of this has to be provided.

- Annex 1, Data protection, number 34. It is made clear that the question of whether the manufacturer has implemented measures for the traceability of changes to data is referring to “personal data stored by the manufacturer”.

- Annex 1, Data security, number 1. The ISMS does not have to proven with a certificate at the request of BfArM until April 1, 2022 (instead of the previous January 1, 2022).

- Annex 1, Data security, number 15a has been added. Digital health applications must support secure digital identity according to § 291 paragraph 8 of SGB V by January 01, 2023. In return, item 6, which required authentication using an electronic health card and contactless interface, was deleted for digital health applications with particularly high protection requirements.

- Annex 2, Interoperability, number 4a has been added with the question of whether profiles created by the manufacturer itself are published.

- Annex 2, Interoperability, number 5 has been added. The digital health application should make it possible (with the consent of the insured person) to transmit data to the ePA, including automatically. This automated mechanism should be configurable and end as soon as the prescribed period ends.